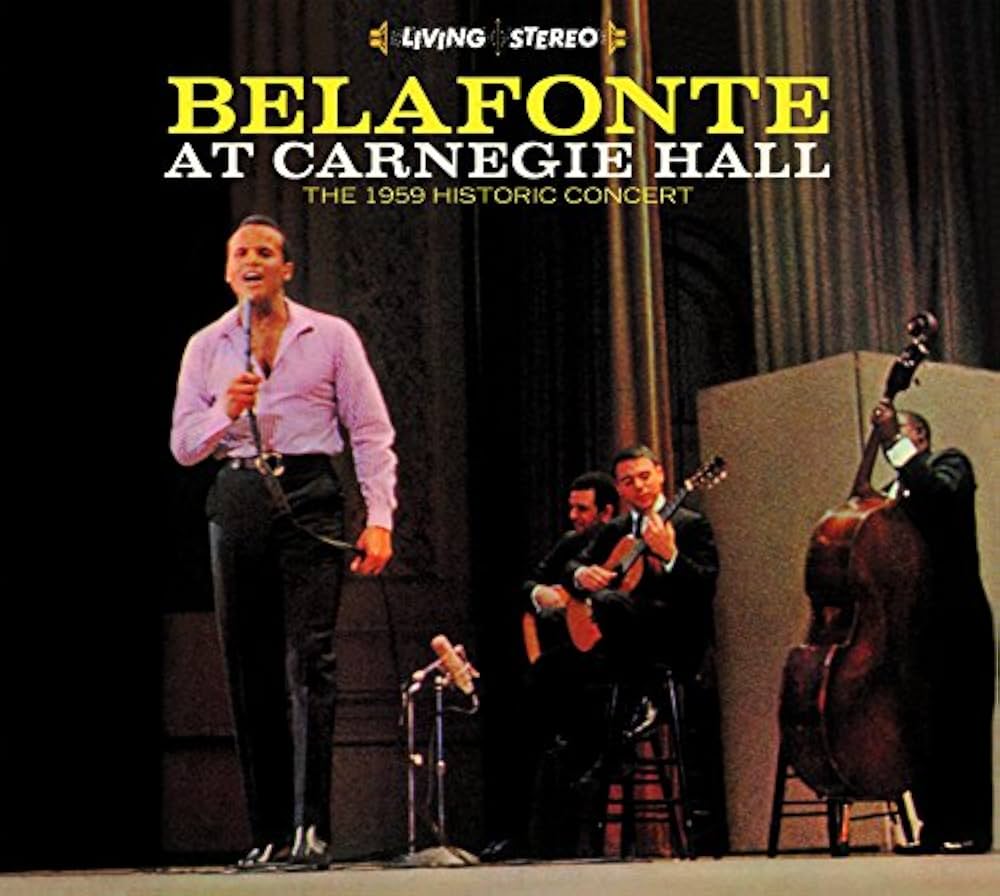

There are “classic” live albums, the ones casual rock fans can rattle off like mandatory reading: Frampton Comes Alive, Live at Leeds, At Folsom Prison, Stop Making Sense. Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall belongs in this grouping

And then there are the albums that quietly sit in the corner, ignored because they don’t fit into the canon built by record stores and Rolling Stone lists.

Harry Belafonte’s two Carnegie Hall albums fall into the second category — not because they’re lesser, but because they refuse to shout.

They’re too generous, too careful, too musically disciplined to elbow their way into the modern conversation, encouraging admiration for their subtle brilliance.

While often overlooked, these albums might be the most beautifully crafted and culturally vital live recordings ever made, and they deserve more recognition.

I. The 1959 Concert: Understatement as Power

The first album, Harry Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, is a masterclass in pacing, tone, and emotional intelligence. Belafonte stands in front of a full orchestra, but he never lets it swallow the intimacy. This is a performer who knows exactly when to lean in and when to pull back — a trait only the very best share.

Act I – Folk Roots with a Storyteller’s Soul

Tracks like “Darlin’ Cora” and “Cotton Fields” land with a quiet gravity. Belafonte was not a folk singer in the strict sense — he was a narrator.

He treats these songs the way an actor treats a monologue: reveal a layer, pause, let the audience breathe.

Act II – Calypso, But Not a Calypso Show

Most people think they know Belafonte because of “Day-O.”

This album politely corrects that assumption.

When he finally performs “Jamaica Farewell” or “Day-O,” they function not as hits but as aesthetic pillars — cultural roots offered without gimmick or exaggeration. If anything, the restraint adds weight. He doesn’t perform calypso like a novelty act. He performs it like heritage.

Act III – Spirituals & Deep Wounds

By the final section, he goes to places the casual fan would never expect from the “Banana Boat Song” guy.

Spirituals. Laments. Songs with centuries in their bones.

This is where the album reveals itself: Belafonte was always a politically aware artist, but here it’s expressed not with slogans, but with the quiet insistence of lived history.

II. The 1960 Album: Belafonte the Curator

Where the first album is Harry Belafonte the Artist,

The second — Belafonte Returns to Carnegie Hall — is Harry Belafonte the Connector.

He hands the spotlight around freely, and the result is extraordinary. This is an album so rich and varied it feels like a festival compressed into two sides of vinyl.

Miriam Makeba – A Revelation

Makeba was still early in her U.S. career when Belafonte introduced her here.

She doesn’t just sing — she changes the temperature of the room.

Her phrasing, her rhythmic sense, her stage presence, this wasn’t just a guest spot.

It was a cultural moment.

Her performances on this album are the earliest recorded proof that she was destined to become an international icon.

The Chad Mitchell Trio – Precision, Politics, and Perfect Harmony

Belafonte hands the stage to three guys who could harmonize like they had a single lung between them. They’re sharp, witty, musically airtight, and criminally overlooked today.

They don’t try to outshine Belafonte — they complement him.

The Trio add a youthful brightness and political edge that foreshadows the folk revival still to come.

Odetta – A Voice That Could Split Stone

And then there’s Odetta.

Not including her would be a crime.

Her voice carries authority, dignity, and sorrow in equal measure — like she’s channelling something older than the building she’s singing in.

Her appearance on this album is one of those “stop what you’re doing and just listen” moments.

Odetta didn’t need vocal fireworks. She was the fire.

“There’s a Hole in My Bucket” – Comedy Performed by Masters

Then, the curveball:

Harry Belafonte and Makeba perform “There’s a Hole in My Bucket” — and it’s hilarious, precise, and completely disarming.

Two world-class vocalists performing a children’s dialogue song shouldn’t work.

And yet it’s perfect.

Their comedic timing is killer.

Their chemistry is evident.

It shows a different side of them — playful, warm, slightly ridiculous — and the audience eats it up.

It’s a reminder that great performers don’t just sing well.

They hold spaceconnect. They invite you in.

III. What Makes These Albums Historic

These albums capture a pivotal cultural moment before the British Invasion, the folk boom, and ‘world music,’ helping us understand the roots of modern musical diversity.

Before the folk boom.

Before “world music.”

Belafonte helped open the door to it all.

2. They show the power of generosity in artistry

These albums are not ego trips.

They’re communal expressions — built on respect.

They prove that quiet brilliance lasts longer than hype, inviting the audience to appreciate understated mastery over flashiness. Belafonte wasn’t selling rebellion.

He wasn’t selling glamour.

He was selling humanity.

And in retrospect, that’s the more revolutionary move.

IV. Why Nobody Talks About Them

Because Harry Belafonte doesn’t fit into the modern genre boxes.

He wasn’t “folk enough” for the folk canon.

Not “pop enough” for the pop canon.

Not “world enough” for the world-music crowd.

He lived at the intersections — and intersections rarely get the headlines.

V. Why You Should Listen Today

Put on good headphones.

Lights low.

Start with the first album front to back.

Listen to the pacing, to the audience responses, how he moves from passion to humour to sorrow without ever breaking the flow.

Then jump to the 1960 album and let the variety wash over you:

Harmonies, African vocal lines, orchestral folk arrangements, comedy, spirituals, and political undertones.

Together, the two albums form one of the most complete portraits of an artist ever captured on tape.

VI. Final Word

Harry Belafonte didn’t just step onto the Carnegie Hall stage.

A world where cultures met, where voices intertwined, where the spotlight was a shared resource instead of a weapon.

Most live albums try to immortalize a performance.

These two immortalize a moment.

It’s time they were remembered for what they truly are:

Two of the greatest underplayed live albums ever made.